As I mentioned in a recent post, my trip to the UK last summer was specifically to research John Pickett Mystery #9, Into Thin Eire. Still, I already knew what Book 10 would be about, and one of my experiences on this trip provided a spark for that book as well. For while I was in London, I went mudlarking!

As I mentioned in a recent post, my trip to the UK last summer was specifically to research John Pickett Mystery #9, Into Thin Eire. Still, I already knew what Book 10 would be about, and one of my experiences on this trip provided a spark for that book as well. For while I was in London, I went mudlarking!

In case you’re unfamiliar with the term, mudlarking was an early form of recycling in which people, often children (called mudlarks), scavenged along the exposed riverbank of the Thames at low tide for anything they could sell. John Pickett was an occasional mudlark in his misspent youth, so I thought it would be fun to try something that he would have done. (The other option, pickpocketing, is, alas, frowned upon.)

I went online to learn what I could about modern-day mudlarking, and discovered that, for one thing, you have to have a permit from the London Port Authority. I also learned that they don’t recommend you go by yourself. If you do, you should at least be aware at all times of the location of the nearest stairs; when the tide turns, the river rises very swiftly, and it’s possible to be cut off.

So I searched for a guide to take me out. (Another advantage of going with a guide is that he has the permit issue taken care of.) I eventually made a date with Steve Brooker (aka the “mud god”), who’s been featured on the History Channel and written up in Time magazine and elsewhere. But while searching, I came across an article on mudlarking that quoted a curator at the Museum of London as saying (I’m quoting here as nearly as I can remember), “almost everything we know about childhood in the Middle Ages comes from finds the mudlarks have brought in.” It’s often said that times may change, but human nature doesn’t. Children lose things, whether in the twelfth century or the twenty-first.

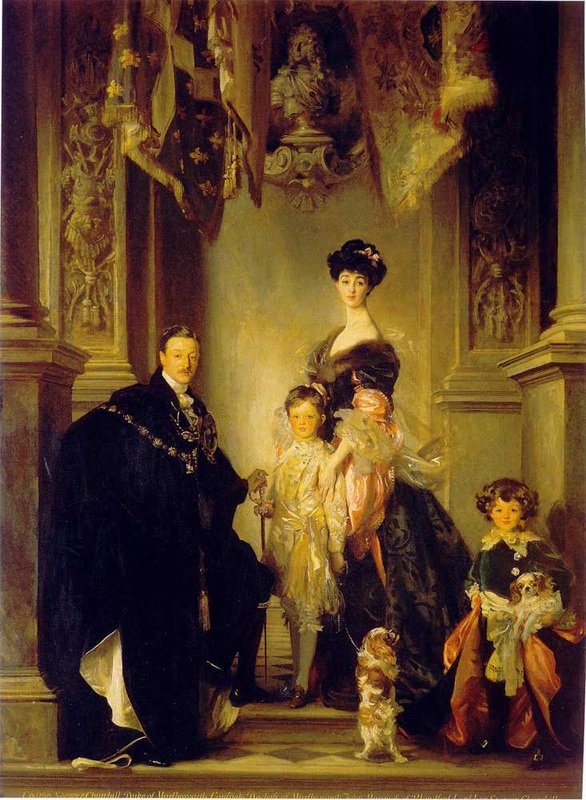

The skyscrapers in the background make up the

Canary Wharf business district on the Isle of Dogs.

Still, the idea of those toys, lost somehow in or along the river only to be washed up decades or even centuries later, started me thinking. In Book 10, Brother, Can You Spare a Crime?, John Pickett discovers he has a ten-year-old half-brother. That half-brother, I knew, would have had an upbringing very similar to John’s; what if he, too, had been an occasional mudlark, and had found a toy of some kind—one not necessarily of any monetary value, but something that he, a poor child having so little, prizes? And what if he (like all those medieval children) dropped it—not in the River Thames, but at the scene of a crime? I hadn’t even gone on my own mudlarking adventure yet, but thanks to the internet, I already had a head start on my next book!

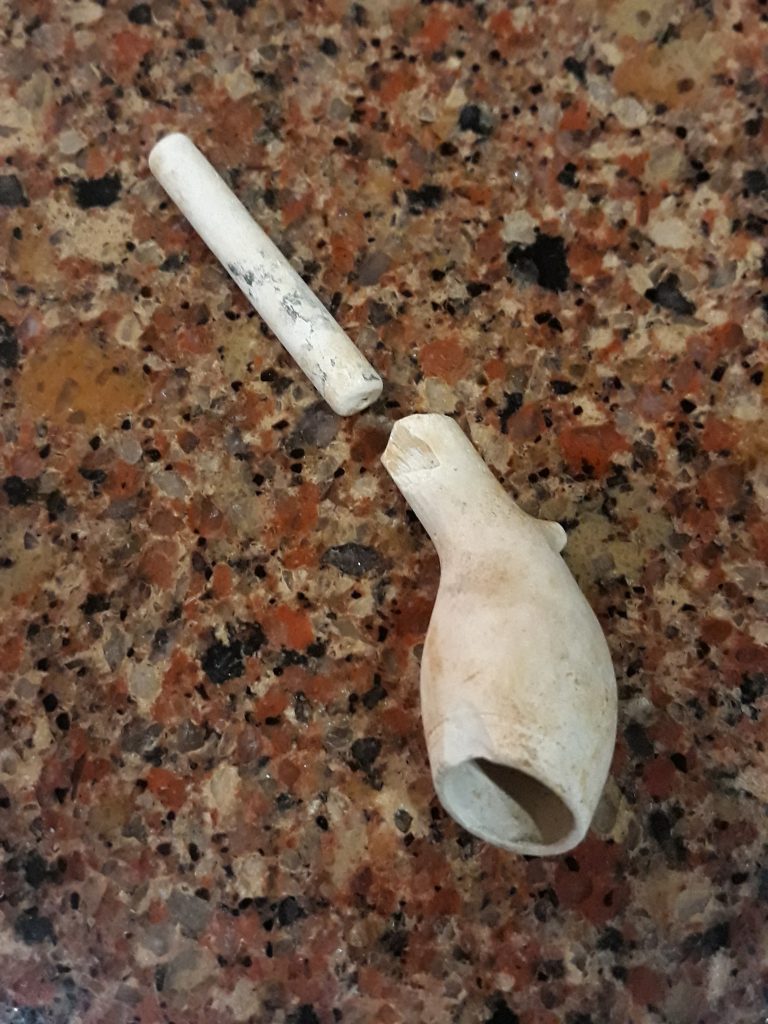

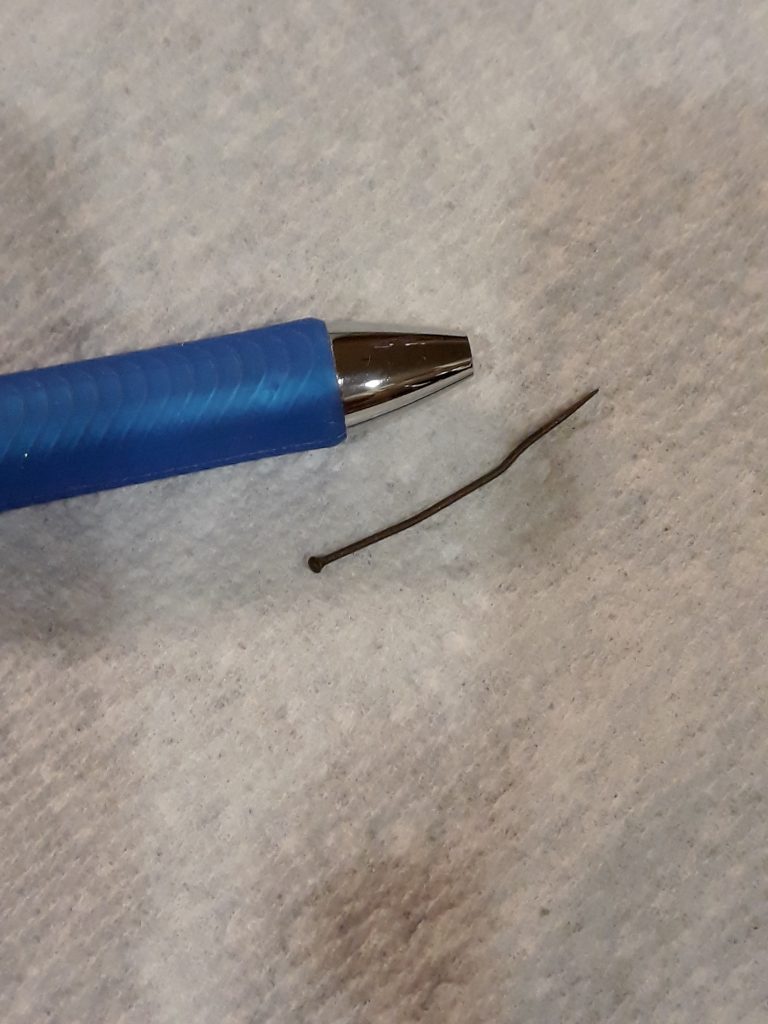

You’ll be able to see how this element fits into the book when it releases on June 12, but in the meantime, here are a few photos of my own mudlarking finds. Contrary to what you might expect, we did not use a metal detector (in fact, the “mud god” has strong views about the use of metal detectors along the foreshore, and the role they play in erosion); instead, he taught me how to read the tides as the nineteenth-century mudlarks would have done.

I met up with Steve in Greenwich at the Cutty Sark, and we walked through the tunnel beneath the Thames to the Isle of Dogs, the peninsula formed by a deep bend in the river east of the City. (Incidentally, whenever you see London referred to as the “City”—capitalized—it refers to the portion of central London, roughly one square mile, that was once contained within the old Roman wall.) Why that particular spot? Because once upon a time, the Isle of Dogs was the site of a dumping ground for one of Henry VIII’s palaces. Dead people’s garbage dumps are a historian’s playground; so much can be learned by what people threw away, either by accident or deliberately. Which makes me wonder what historians will learn about us someday, but that’s a topic for another blog, written by another blogger.

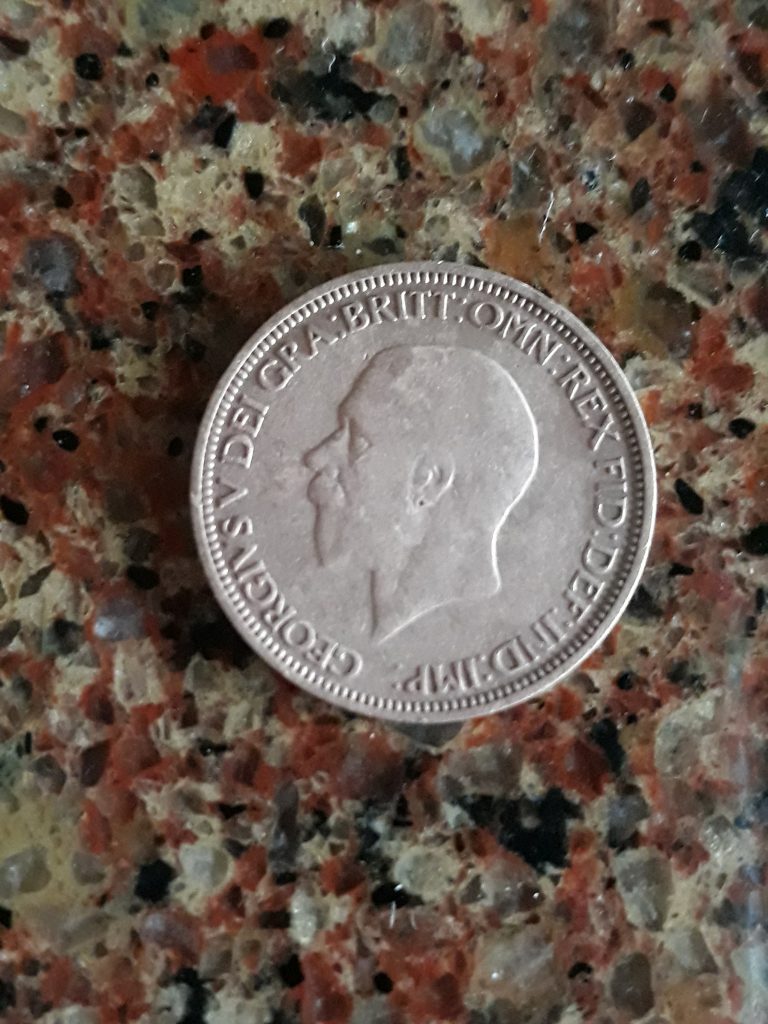

THE PHOTOS:

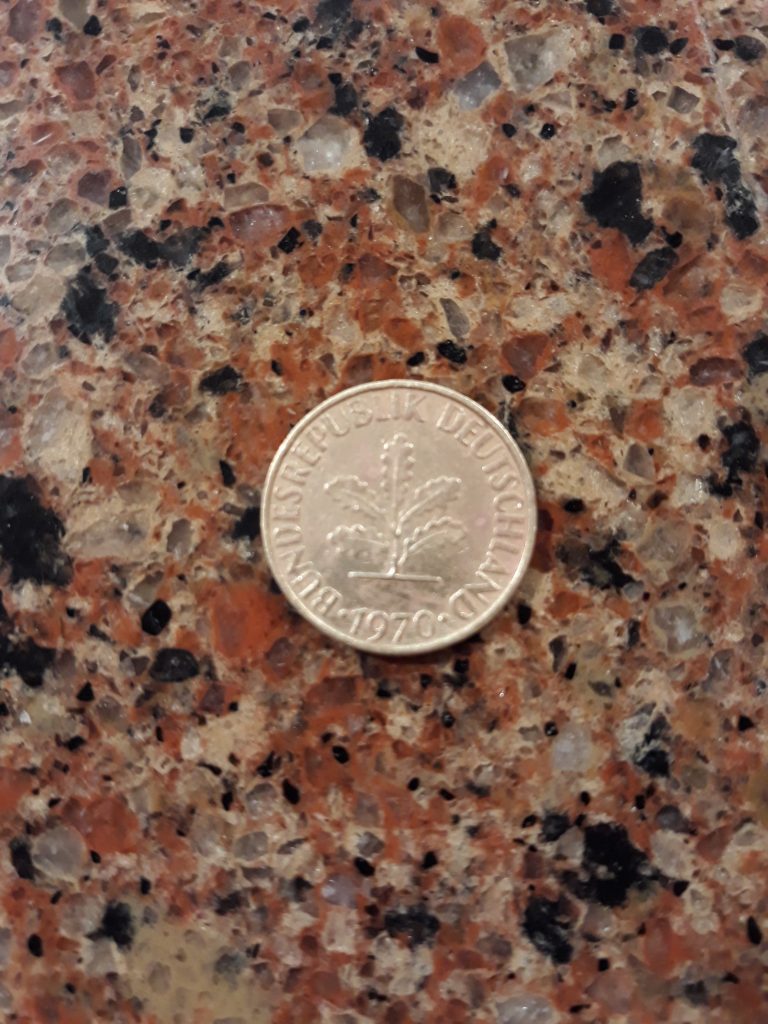

The reverse side gives the date as 1900.

just a bit larger than a US quarter.

100 pence = 1 pound. (The half-penny was not removed from circulation until 1984.)

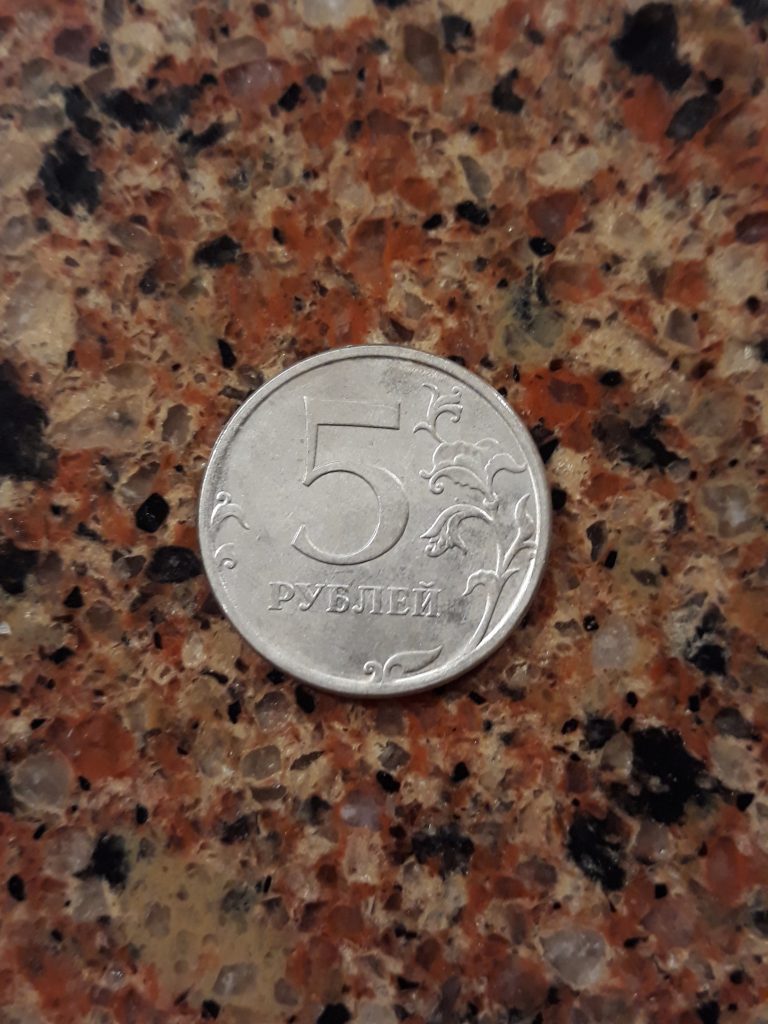

There was more, including modern coins from the UK as well as a US quarter, a small brass button, a number of 19th-century nails. . In fact, I haven’t yet got around to cleaning it all! We were on the foreshore for about two hours before the tide made it necessary for us to curtail our hunt. Here’s a photo of all our finds:

I can’t wait to go again! Hmm, I wonder what I’ll find next time…