Now that I had a high-waisted gown and pelisse (see my previous post, The Making of a Regency Costume, Part 1), it was time to focus on the accessories that would turn it into an authentic-looking Regency costume. The biggie, of course, was the bonnet. There are numerous websites and YouTube videos showing the various stages of bonnet construction; although I watched many of these (including this one from Stephanie Johanesen of the Oregon Regency Society) I found the websites that showed still photos more helpful, as I didn’t have to keep reaching for the “pause” button on my phone. I liked this site, with one caveat, which I’ll explain below.

I saw one potential problem right away. While my dress/pelisse pattern had been very specific, all the bonnet tutorials were extremely vague as to measurements: “ . . . or you can make it bigger or smaller . . .,” etc. Fortunately, I was making my bonnet only a few weeks before Easter, which meant that the “Everything’s $1” store had cheap straw bonnets for $1. This was a very good thing for me, since the only 18-inch bonnet I had found was at Michael’s, and had cost about $10—much more than the $3 price quoted in the blog above. The 40%-off coupon brought it down some, but all the same, I bought a second hat from the dollar store. It didn’t look historically accurate by a long chalk—the “straw” was actually some kind of plastic—but it would serve as a practice piece.

And a good thing, too. When making the practice hat, I cut away about a third of the hat as per the instructions on the Better Dresses Vintage blog, and finished the cut raw edge with wide bias tape. At this point, I tried on the hat, and suffered my first setback: the brim stuck out weirdly over my ears at the “corners” where the brim was cut away. I continued to work on my practice bonnet, but I was pretty sure that, unless something changed drastically by the time I was finished, it would be a wash.

So I plowed gamely on, first lining the inside of the brim with a fine voile and, finally, cutting a rectangle of fabric for the crown. As my instructions said it should be 9 inches when folded, I cut it to 18 inches, folded the piece, and continued. To my chagrin, the crown was so small that I couldn’t even get it to cover my head! It was at this point that I tossed my practice bonnet aside. It was obviously beyond hope, but I’d learned a lot about construction—the biggest lesson being that, whether it’s the straw brim or the fabric crown, while you can always cut off more, you can’t put it back on.

The straw hat, showing the chunk(s) I cut out of the brim.

That’s why, when I cut into my “real” hat (after covering my work surface with newspaper; after all, my “real” hat was made of “real” straw!), I only cut out a small section of the brim, leaving the crown intact. (And after trying it on, I cut out a bit more, as you can see in the photo.) I pinned a length of extra-wide double-fold bias tape in place and secured it with a hot-glue gun, although if I had it to do again, I might have sewn it; in some of the later steps, I did use a sturdy needle and thread, and it would have been a lot easier if I hadn’t had to work around those patches of glue.

Finishing the raw edge & around the brim with bias tape. Some of the websites I consulted suggested using ribbon, but I thought extra-wide double-fold bias tape would conform to the curved shape of the brim without so much puckering.

The brim is lined by gathering a lightweight voile at the brim edge, and again where the brim meets the crown, and sewing in place with a sturdy needle; thread should match the hat, not the voile, in order to be invisible from the outside. (It might be covered up by trim anyway, but why take chances?) I didn’t trim the excess (it would have been a ravelly mess if I had), but simply stuffed it inside the crown.

Still, it looked much better this time when I tried it on. I added a double ruffle of gray-green tulle*, and when I lined the brim with voile, I positioned it so that about an inch hung over the brim.

*A word here about colors: I mentioned in my last post that, although my pelisse was gray, I didn’t want to look like a lady wearing half-mourning. I was also going on the assumption that most Regency ladies wouldn’t have a different bonnet to go with every outfit, so I didn’t try to go all matchy-matchy with the bonnet colors. Instead, I decided to go with ribbons, crown fabric, etc. in a shade of green that would coordinate with, but not exactly match, the greens in the print fabric I’d used for the dress.

Now it’s starting to look like a real bonnet!

For the fabric crown, I wanted something with enough body that it would hold its shape, but not be too thick for all the gathering I would have to do. One of the websites I’d studied suggested taffeta; unfortunately, I couldn’t find any. I finally settled on a crepe-backed satin, and folded it inside out, with the shiny side to the inside. I’d also learned the hard way that a 9-inch-deep crown wouldn’t begin to cover my big head, so I didn’t cut it at all, figuring I could trim it down to size as I went along. But I never did; I used that entire yard of fabric (folded in half, of course). If you’re making a bonnet of your own, be aware that the crown fabric is greatly reduced in size by the gathering process! I wanted lavish gathering rather than a skimpy crown (don’t want to appear shabby-genteel, you know!), and it took every bit of that fabric to achieve the desired effect.

The photo (above) shows the crown gathered to the hat before it’s all covered up with trim. After this picture was taken, I hot-glued a length of 5/8-inch single-fold bias tape (in the same color as the wide bias tape finishing the brim edge) over the gathering stitches to conceal them. You can also see in this photo how the ribbon tie works. (By the way, the gold ribbon shown here is a leftover from my practice piece; it’s not the one I used in the final version.) Rather than attach two lengths of ribbon to the “corners” of the brim where it’s been cut away, I left the ribbon tie in one long piece, centered it over the front of the bonnet, and simply draped it over the brim where it meets the crown, then tied it in a bow beneath my chin, being sure to pull it tightly enough to bend the brim into the proper shape.

The finished product!

This front view shows the interior trim.

Before that, though, I had to trim the bonnet. I bought two branches of artificial peonies in an off-white shade to match the bias tape and voile I’d used for the brim lining. I cut off three of the larger flowers and tacked them securely to the crown, then cut off the half-open buds and tacked them to the inside of the brim, being sure to stitch all the way through both voile and the brim itself. I used a thread that matched the straw, so the stitches don’t show from the outside.

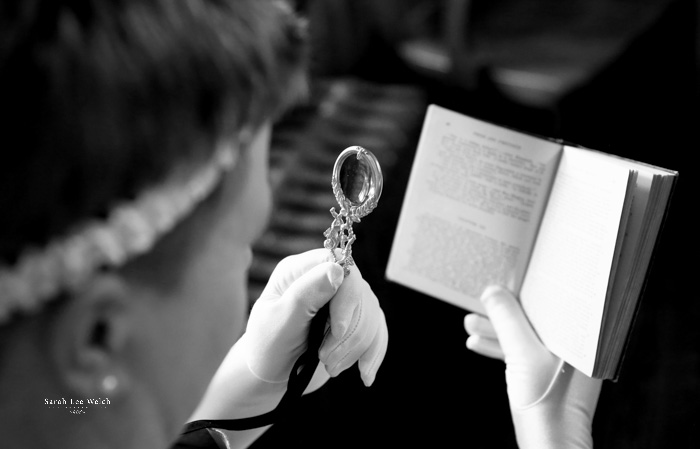

“Still Life with Bonnet and Quizzing Glass.” Here you can see the gathering at the crown.

In Part 3, I’ll talk about accessories: reticule, fingerless gloves, and a headpiece for evening wear that would stay in my very short hair!