Like many writers, I majored in English in college. I was that student who always asked, “Did Famous Dead Author really mean that wilting houseplant to be a symbol of death, or was that interpretation concocted by English teachers and college professors in an attempt to burnish his credentials as a Great Writer?” In other words, did the author in question think, “I believe I’ll add a dying aspidistra in the corner to give sharp-eyed readers a hint as to Nigel’s ultimate end.” Or was he merely trying to tell a good tale, and figured Nigel was just the sort of guy who would forget to water his plants? To paraphrase what Freud never actually said, sometimes a houseplant is just a houseplant.

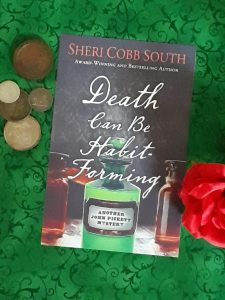

Death Can Be Habit-Forming, John Pickett Mystery #11

Fast-forward more years than I care to count to 2020. I struggled to write during the pandemic, so much so that Death Can Be Habit-Forming, originally scheduled for March 2021, was postponed to May/June and then, when it became clear that I still wouldn’t have the book finished, to late August. Amazon is quite punitive to authors who don’t have their books uploaded by the deadline (about three days before the book’s publication date), so the pressure was on to finish with last-minute edits and submit the file. I’m pleased to say that I made the deadline—albeit by a scant two hours!

In this book, John Pickett Mystery #11, Pickett arranges to be committed to an asylum for opium-eaters in order to rescue a woman being held there against her will. He soon discovers that getting in was the easy part; getting out may prove to be another matter entirely.

As the last step before uploading the manuscript to Amazon, I used my laptop’s text-to-speech feature to listen to the entire 83,000-word manuscript over the course of three days; I’ve discovered that, since it reads back exactly what I typed, rather than what I “meant” to say, nothing works as well for catching the typos my eye tends to skim over.

But being so deeply immersed in the story over a short period of time with very few breaks, I noticed something I hadn’t before, something I hadn’t even noticed I was doing.

The pandemic, and the related lockdown, was there, permeating every line.

I knew, of course, that I’d included a reference to the recently developed smallpox inoculation. This was mostly plot-related; I’d needed a reason for John Pickett’s wife, Julia, to see something in the window of a shop in a part of London where she would not normally venture. Since the discovery and rescue of John’s previously unknown half-brother, Kit, had been the premise of the previous novel (Brother Can You Spare a Crime?, winner of the 2021 Colorado Authors League’s Award of Excellence in the Action/Adventure category), I decided she might need to consult with Kit’s dreadful mother on something. The challenge of finding a reputable school willing to take a pupil of Kit’s background is established early in the book, partly as comic relief and partly as one of the more quelling aspects of taking a child of the slums into Julia’s Mayfair household. Determining Kit’s inoculation status was a natural outgrowth of that situation.

Actually, I have no idea if the British “public schools” (ironically, what Americans would call private schools) had any policies one way or another regarding inoculation. Fortunately, since I was not using one of the existing schools such Eton or Harrow (acknowledging within the text that neither of these prestigious establishments would touch Kit Pickett with a ten-foot pole!), I could make up the rules to suit myself; such is the advantage of authorship.

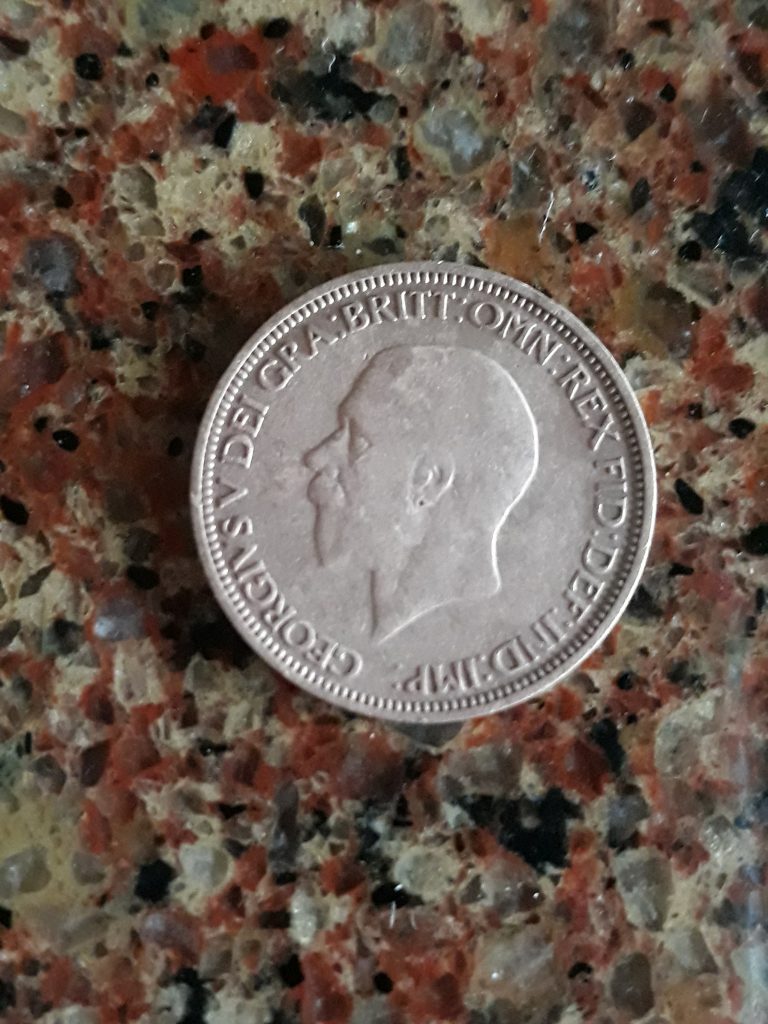

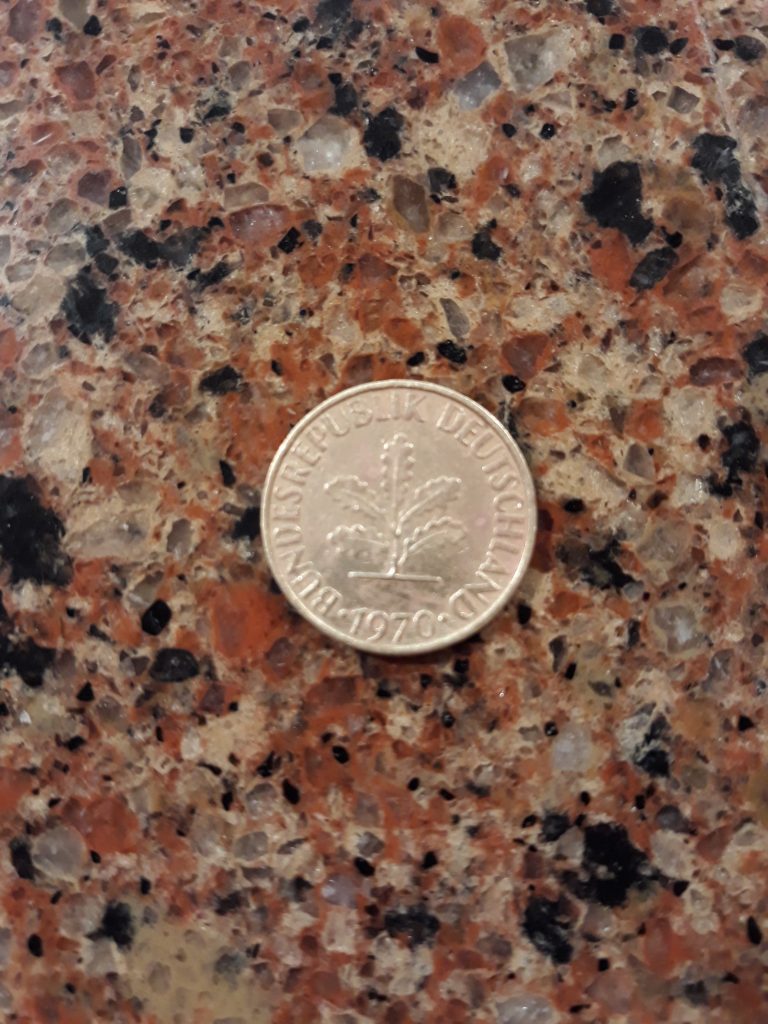

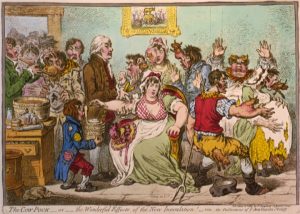

“The Cow-Pock–or–the Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation!” James Gillray, June 12, 1802

Doing a quick check on the internet to confirm my recollections of the date of the smallpox inoculation, I was reassured to find that the use of cowpox matter as a preventive against smallpox was first discovered by Edward Jenner, an English doctor, in 1796 and made available to the general public in 1798, so it suited my purposes very nicely. To my surprise, however, I learned that people then were just as wary of the inoculation as many are of the COVID vaccine today—although while the vaccine-hesitant today generally cite the haste with which it was developed and/or the lack of knowledge of any potential long-term effects, those in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were afraid it might turn them into cows! In fact, there’s a wonderful cartoon by James Gillray from 1802 that shows a man, presumably Jenner, preparing to inoculate a nervous-looking woman with a substance labeled “Vaccine Pock hot from ye Cow,” while others, having undergone the same treatment, watch with dismay as small cows erupt from their arms, legs, and noses. A man on the far right has sprouted horns on his head, and a woman on his right appears to be pregnant. (Don’t tell me Gillray didn’t mean to imply that she was about to give birth to a calf, for I won’t believe you!)

The introduction of the smallpox inoculation into my book was a deliberate choice, albeit one that probably would not have occurred to me had the COVID vaccine not been so much in the news lately. But I hadn’t realized how closely John Pickett’s confinement reflected my own sense of isolation as the lockdown dragged on past the early talk of staying home for a few weeks in order to “flatten the curve” to a vague sense of going back to normal “someday” after a vaccine was developed.

In the book’s second act, Pickett becomes increasingly convinced that both his wife and the woman he has come to rescue are being deliberately kept from him. It’s no coincidence that I was writing those chapters just as the autumn spike in COVID cases put paid to my own hopes of being able to fly home to celebrate Christmas with my family; “Authority,” in the form of the CDC, WHO, and the ubiquitous Dr. Fauci, was conspiring to keep us apart, just as Mrs. Danvers, the sinister proprietress of the Larches, was doing to poor John Pickett.

I still don’t know the true meaning of that aspidistra wilting in the corner of Nigel’s living room, but I can testify that Death Can Be Habit-Forming reflects, and was influenced by, current events in a way none of my earlier works have been.

I only hope that we, like Pickett, will soon be set free.

[For more on writing in the midst of a pandemic, check out Bookstr’s roundtable discussion on this timely subject featuring five authors, of whom I am one: “Pandemic Writing: 5 Authors Reveal Covid’s Influence”]