Alva Erskine Smith (later Vanderbilt) as a young woman.

Alva Erskine Smith (later Vanderbilt) as a young woman.

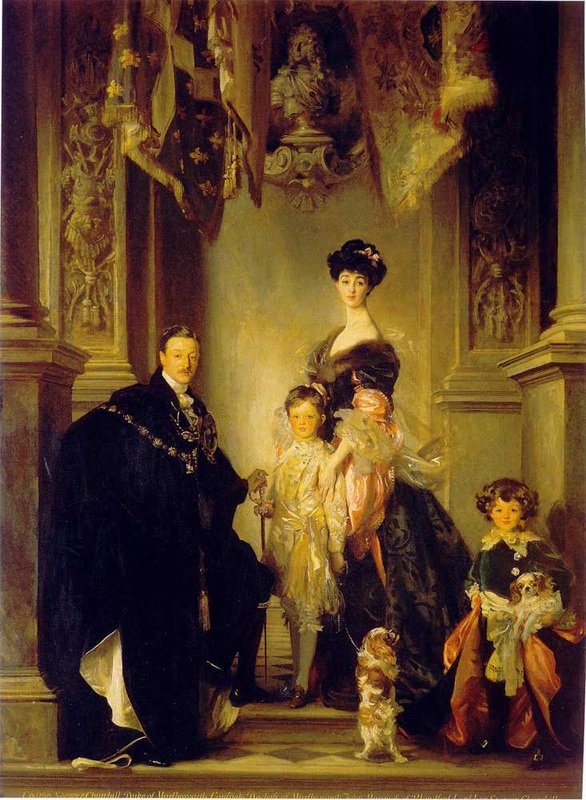

Meanwhile, back in merrie olde England, the Spencer-Churchills, dukes of Marlborough, needed money—again. The magnificent Blenheim Palace had been constructed between 1705 and 1722 as a gift to the 1st Duke of Marlborough in gratitude for military victory over the French and Bavarians. It had been an albatross around the family’s necks ever since. The house—so huge that if its wings could be folded out straight, the façade would measure half a mile in length—required constant infusions of cash. What to do? Why, what every titled Englishman in need of funds was doing in the late 19th century: marry an American heiress. Charles Spencer-Churchill (aka “Sunny”), the 9th duke, looked about him for a likely candidate, and found Consuelo Vanderbilt and her railroad millions.

He could not have asked for a more formidable ally than his prospective mother-in-law. Almost from the moment of Consuelo’s birth, Alva had been grooming her daughter to make a brilliant marriage, and no marriage could possibly be more brilliant than one to a duke, the highest level of British aristocracy. And not just any duke, but the Duke of Marlborough, whose wife would be mistress of Blenheim Palace. The drawback that Consuelo was in love with someone else? Unimportant. The fact that Sunny, at only five feet six inches tall, was shorter than his bride—ludicrously so when she was dressed in the high heels and large hats of the day? Insignificant. Alva wanted the Duke of Marlborough for Consuelo, and that was the end of it.

Consuelo, only eighteen years old, was no match for her mother’s ambition. And so she and Sunny were married on November 6, 1895, with the future duchess in tears as she marched down the aisle. Of course, she was expected to ensure the succession by giving birth to a son. In the meantime, the duke’s heir presumptive was his second cousin, Winston. (Yes, Winston. Of the Spencer-Churchills. You figure it out.) Sunny’s grandmother put it to Consuelo in no uncertain terms: “Your first duty is to have a child, and it must be a son, because it would be intolerable to have that little upstart Winston become Duke.”

Consuelo, Duchess of Marlborough, outdid herself. She not only had a son to inherit; she had two, and it was she who coined the term “heir and the spare.” Since it was obvious that he would never be Duke of Marlborough, young Winston Churchill was obliged to find something else to do with his life—something appropriate for a scion of one of England’s greatest families. Something like, oh, politics. The rest, as they say, is history. Alva and Winston were not related by blood, but they had the same bulldog tenacity. Had anyone else been Prime Minister during World War II, who knows what would have been Britain’s fate—and, by extension, America’s?

And that is how a social climber from Mobile, Alabama changed the history of the world.

I loved it, Sherri

Thank you!

Interesting post. I’m curious to know who was Alva Erskine Smith Vanderbilt’s mother?

Fascinating, thanks for sharing Sheri.

Love it. How things come together. Alabama and England through marriage and the need of money.